Master Time in Chinese: Complete Guide

Written by

Ernest Bio Bogore

Reviewed by

Ibrahim Litinine

Time mastery represents the difference between conversational competence and fluency frustration. Every Chinese learner encounters the moment when someone asks the time, schedules a meeting, or discusses daily routines—and suddenly realizes their vocabulary gaps. This comprehensive guide eliminates those gaps through systematic instruction that builds from foundational concepts to practical application.

The ability to express time naturally in Chinese extends far beyond basic vocabulary memorization. It requires understanding cultural nuances, structural patterns, and contextual usage that native speakers internalize from childhood. Most language learning resources treat time-telling as a simple vocabulary exercise, missing the deeper linguistic patterns that separate functional communication from authentic expression.

Understanding Chinese Time Structure

Chinese time expressions follow a logical hierarchy that differs fundamentally from English approximations. Where English speakers might casually say "around four-thirty," Chinese demands precision through specific linguistic markers that indicate hours, minutes, and temporal relationships.

The foundational vocabulary establishes this precision:

- 时间 (shíjiān) serves as the general term for "time"

- 时 (shí) indicates hours in formal contexts

- 分 (fēn) specifies minutes with mathematical precision

- 秒 (miǎo) measures seconds for exact timing

- 点 (diǎn) functions as the primary hour marker in conversational speech

- 半 (bàn) represents the half-hour mark

- 刻 (kè) indicates quarter-hour divisions

This systematic approach reflects Chinese linguistic philosophy where specificity prevents ambiguity. Unlike English time expressions that rely heavily on context, Chinese time-telling maintains clarity through explicit grammatical markers.

The basic structure follows a predictable pattern: [Time period] + [Hour number] + 点 + [Minute specification]. This framework provides the foundation for all time expressions, from simple hour announcements to complex scheduling discussions.

The Hour Framework: Beyond Basic Numbers

Chinese hour expression reveals the language's preference for contextual precision over numerical simplicity. The structure centers on 点 (diǎn), which literally means "point" but functions as the standard hour indicator in spoken Chinese.

Hours follow the pattern: [Number] + 点 (diǎn). For example, 五点 (wǔ diǎn) indicates five o'clock, while 八点 (bā diǎn) represents eight o'clock. This system applies consistently across all twelve hours, creating a reliable framework for time expression.

The linguistic logic becomes clear when examining the relationship between formal and conversational usage. While 时 (shí) appears in formal written contexts, 点 (diǎn) dominates everyday speech because it creates more natural conversational flow. Native speakers instinctively choose 点 (diǎn) for its phonetic clarity and cultural familiarity.

This hour framework serves as the anchor point for all additional time specifications. Whether adding minutes, indicating half-hours, or incorporating temporal context, the hour + 点 (diǎn) structure remains constant, providing learners with a reliable foundation for building more complex time expressions.

Minute Precision and Special Cases

Chinese minute expression demonstrates the language's commitment to mathematical accuracy in time-telling. The system operates on explicit numerical counting rather than approximation, requiring speakers to state exact minute values rather than rounding to nearest five-minute intervals.

The standard minute pattern follows: [Hour] + 点 + [Minute number] + 分 (fēn). For instance, 七点十八分 (qī diǎn shíbā fēn) precisely indicates 7:18, while 九点二十六分 (jiǔ diǎn èrshíliù fēn) specifies 9:26. This precision reflects Chinese cultural values regarding punctuality and accuracy.

However, conversational Chinese allows for 分 (fēn) omission in many contexts. Native speakers frequently drop the minute marker when the context makes the meaning clear, saying 七点十八 (qī diǎn shíbā) instead of the full form. This linguistic economy creates more natural speech flow while maintaining clarity.

The critical exception involves the ten-minute mark, where 分 (fēn) cannot be omitted. Saying 三点十 (sān diǎn shí) for 3:10 sounds incomplete and potentially confusing to native speakers. The correct form requires 三点十分 (sān diǎn shí fēn), maintaining the minute marker for phonetic completion and semantic clarity.

This exception exists because single-digit minute expressions (一 through 九) naturally flow without 分 (fēn), while ten (十) requires the minute marker to distinguish it from other potential meanings. Understanding this distinction prevents common learner errors and improves conversational authenticity.

Special Time Markers: Half and Quarter Hours

Chinese employs specific markers for common time divisions that streamline expression while maintaining precision. These markers replace longer numerical expressions with concise, culturally established terms that native speakers prefer in casual conversation.

半 (bàn) indicates the thirty-minute mark across all hours. Instead of saying 六点三十分 (liù diǎn sānshí fēn), speakers use 六点半 (liù diǎn bàn) for 6:30. This pattern applies universally: 十点半 (shí diǎn bàn) for 10:30, 十一点半 (shíyī diǎn bàn) for 11:30, and so forth.

The half-hour marker cannot be omitted or replaced with numerical alternatives in standard conversation. While both forms remain grammatically correct, native speakers strongly prefer 半 (bàn) for its natural sound and conversational efficiency.

刻 (kè) serves as the quarter-hour marker, though its usage patterns differ from 半 (bàn). For fifteen minutes past the hour, speakers say 五点一刻 (wǔ diǎn yī kè) meaning "one quarter past five." This construction uses 一刻 (yī kè) to indicate the first quarter-hour division.

The quarter-hour system theoretically extends to three-quarters (三刻), but actual usage varies significantly across regions and speakers. Many native speakers prefer numerical expression 九点四十五分 (jiǔ diǎn sìshíwǔ fēn) for 9:45 rather than 九点三刻 (jiǔ diǎn sān kè), making the three-quarter form less essential for learners to master initially.

The Two O'Clock Exception

Chinese number usage reveals a fascinating linguistic complexity when addressing two o'clock and related times. This exception demonstrates how contextual application can override general numerical patterns, creating a specific rule that affects all time expressions involving the number two.

Standard Chinese counting follows the sequence 一 (yī), 二 (èr), 三 (sān), with 二 (èr) serving as the primary form for the number two. However, time expressions substitute 两 (liǎng) for 二 (èr) when indicating two o'clock or any time containing two hours.

The correct expression for 2:00 becomes 两点 (liǎng diǎn) rather than 二点 (èr diǎn). This pattern extends to all two-hour combinations: 两点十五分 (liǎng diǎn shíwǔ fēn) for 2:15, 两点半 (liǎng diǎn bàn) for 2:30, and 两点四十分 (liǎng diǎn sìshí fēn) for 2:40.

This distinction exists because 两 (liǎng) specifically indicates "two of something" while 二 (èr) represents the abstract number two. Time expressions require the concrete "two hours" concept rather than the mathematical abstraction, making 两 (liǎng) the natural choice for native speakers.

The exception applies only to hour expressions, not minute specifications. When stating 1:22, speakers use 一点二十二分 (yī diǎn èrshí'èr fēn), employing 二 (èr) within the twenty-two (二十二) minute expression. This selective application requires conscious attention from learners until the pattern becomes automatic.

Understanding this exception prevents a common error that immediately identifies non-native speakers. Native Chinese speakers notice incorrect two-hour expressions more readily than many other time-telling mistakes, making this rule particularly important for developing authentic-sounding Chinese.

Time Periods and Daily Context

Chinese time expressions gain practical meaning through temporal context markers that specify morning, afternoon, evening, and night periods. These markers transform abstract hour announcements into meaningful schedule communications that reflect daily rhythm and cultural patterns.

The temporal markers follow a precise system:

早上 (zǎoshang) covers early morning hours from midnight through approximately 8 AM, encompassing the period when most people sleep and wake. Native speakers use this term for very early appointments, sunrise activities, and morning routines that occur before regular business hours.

上午 (shàngwǔ) indicates late morning from 9 AM through 11 AM, representing the productive morning period when offices open and formal activities begin. This distinction matters for business scheduling and professional communication.

中午 (zhōngwǔ) specifies the noon period from 12 PM through 1 PM, traditionally associated with lunch and midday rest. Chinese culture places particular emphasis on this period, making accurate expression culturally important.

下午 (xiàwǔ) encompasses afternoon hours from 2 PM through 6 PM, covering the post-lunch productive period and early evening transition. This broad category includes most business meetings and social appointments.

晚上 (wǎnshang) indicates evening and night from 7 PM through 11 PM, representing dinner time, entertainment, and relaxation periods. The term carries social implications about appropriate activities and meeting times.

These temporal markers precede the hour expression: 早上七点 (zǎoshang qī diǎn) for 7 AM, 下午三点半 (xiàwǔ sān diǎn bàn) for 3:30 PM, 晚上九点十五分 (wǎnshang jiǔ diǎn shíwǔ fēn) for 9:15 PM.

The system eliminates the need for AM/PM distinctions while providing more specific cultural context than English equivalents. Understanding these periods helps learners communicate more naturally and avoid scheduling conflicts based on cultural expectations.

Expressing "Past" and "To" the Hour

Chinese offers multiple approaches for expressing time relationships that parallel English "past" and "to" constructions, though the linguistic mechanisms differ significantly. These alternatives provide conversational variety and demonstrate advanced time-telling competence.

The "past" concept uses 过 (guò) as an optional marker indicating time elapsed beyond the hour. For 3:15, speakers can say either 三点十五分 (sān diǎn shíwǔ fēn) or 三点过十五分 (sān diǎn guò shíwǔ fēn), with both forms equally acceptable. The 过 (guò) version adds emphasis to the elapsed time concept.

Quarter-hour expressions demonstrate this flexibility clearly. 四点一刻 (sì diǎn yī kè) and 四点过一刻 (sì diǎn guò yī kè) both indicate 4:15, with the latter emphasizing that fifteen minutes have passed beyond four o'clock. Native speakers choose between these forms based on conversational flow and emphasis preferences.

The "to" concept employs 差 (chà), meaning "lacking" or "insufficient," to indicate time remaining before the next hour. For 3:50, speakers can express this as 三点五十分 (sān diǎn wǔshí fēn) or 四点差十分 (sì diǎn chà shí fēn), meaning "ten minutes lacking to four o'clock."

This construction requires careful attention to hour selection. The 差 (chà) format references the upcoming hour rather than the current hour, making 四点差十分 (sì diǎn chà shí fēn) the correct form for 3:50, not 三点差十分 (sān diǎn chà shí fēn).

The "to" construction appears more frequently with larger minute values (typically thirty minutes or more) where the approaching hour becomes more psychologically relevant than the current hour. Native speakers rarely use 差 (chà) for times like 3:05, preferring straightforward 三点五分 (sān diǎn wǔ fēn) instead.

Asking Time Questions

Chinese time inquiries follow specific patterns that reflect the language's preference for contextual precision over general questioning. The question structures vary based on the level of formality and the specific information sought.

The most common time question uses 几点了 (jǐ diǎn le), literally meaning "what hour has it become?" The particle 了 (le) indicates completed action or current state, making this question appropriate for asking the present time. The response format follows standard time expression patterns: 现在三点半 (xiànzài sān diǎn bàn) meaning "now it's 3:30."

For more specific inquiries, speakers add 现在 (xiànzài) meaning "now" to create 现在几点了 (xiànzài jǐ diǎn le). This version emphasizes the immediate present moment and typically elicits more precise responses including temporal markers: 现在是下午两点二十分 (xiànzài shì xiàwǔ liǎng diǎn èrshí fēn).

The formal response structure incorporates 是 (shì), the copula verb meaning "to be," creating complete sentences rather than fragment answers. This formality level suits professional contexts and stranger interactions where politeness conventions matter.

Regional variations exist in question formation, with some areas preferring 几点钟了 (jǐ diǎn zhōng le) by adding 钟 (zhōng) meaning "clock." However, the standard 几点了 (jǐ diǎn le) form remains universally understood and appropriate across all Chinese-speaking regions.

Understanding these question patterns enables learners to both ask for time information and recognize when others are making time inquiries, improving overall conversational competence in time-related discussions.

Advanced Time Expressions and Scheduling

Professional and social scheduling requires more sophisticated time expressions that go beyond basic hour announcements. These advanced patterns enable precise appointment setting, duration specification, and temporal relationship communication that characterizes fluent Chinese usage.

Duration expressions use specific grammatical structures that indicate time spans rather than specific moments. The pattern 从...到... (cóng...dào...) meaning "from...to..." creates time ranges: 从九点到十一点 (cóng jiǔ diǎn dào shíyī diǎn) indicates "from 9:00 to 11:00." This construction applies to any time span regardless of length or complexity.

Appointment scheduling employs temporal positioning words that specify relationships between events and times. 在 (zài) indicates "at" for specific moments: 在下午三点开会 (zài xiàwǔ sān diǎn kāihuì) means "have a meeting at 3 PM." The preposition creates precise temporal anchoring for scheduled activities.

Approximate time expressions use modifiers that indicate uncertainty or flexibility. 大概 (dàgài) meaning "approximately" creates time estimates: 大概五点半到 (dàgài wǔ diǎn bàn dào) indicates "arrive at approximately 5:30." This construction acknowledges realistic scheduling constraints while maintaining commitment to general timeframes.

Frequency expressions combine time specifications with repetition indicators. 每天早上七点 (měi tiān zǎoshang qī diǎn) means "every day at 7 AM morning," establishing routine patterns. These expressions become essential for discussing regular schedules, habit formation, and ongoing commitments.

Relative time expressions position events in relationship to other temporal reference points. 三点以后 (sān diǎn yǐhòu) means "after 3:00," while 五点以前 (wǔ diǎn yǐqián) indicates "before 5:00." These constructions enable flexible scheduling that accommodates multiple constraints.

Cultural Context and Regional Variations

Chinese time-telling reflects broader cultural values regarding punctuality, precision, and social harmony that influence both expression choices and usage patterns. Understanding these cultural dimensions helps learners communicate more effectively and avoid unintentional social missteps.

Punctuality expectations vary significantly across different Chinese-speaking regions and social contexts. Business environments typically demand exact time adherence, making precise time expressions essential for professional success. Social gatherings may allow more flexibility, but accurate time communication still demonstrates respect for others' schedules.

Regional dialectal influences affect time expression preferences even within Mandarin-speaking areas. Northern regions tend toward more formal constructions, while southern areas often favor abbreviated forms. However, standard Mandarin time expressions remain universally understood regardless of local variations.

Generational differences also impact time-telling patterns. Younger speakers increasingly adopt abbreviated forms and omit traditional markers, while older generations maintain more formal constructions. Learners benefit from understanding both approaches to communicate effectively across age groups.

Digital technology has influenced modern Chinese time expressions, with younger speakers sometimes using numerical formats that mirror digital displays. However, traditional spoken forms remain dominant in most conversational contexts, making mastery of standard patterns essential for comprehensive communication ability.

Practical Application and Skill Development

Effective time-telling mastery requires systematic practice that progresses from basic pattern recognition to natural conversational integration. The development process should emphasize accuracy first, then fluency, finally incorporating cultural appropriateness and natural expression.

Number familiarity forms the essential foundation, particularly for numbers one through sixty since these appear most frequently in time expressions. Learners should achieve automatic recognition and production of these numbers before attempting complex time constructions.

Pattern drilling helps establish the grammatical frameworks that support accurate time expression. Practice should include hour announcements, minute specifications, temporal markers, and question-answer patterns until these become automatic responses rather than conscious constructions.

Contextual practice integrates time expressions into meaningful communication scenarios. Role-playing exercises involving appointment scheduling, daily routine discussions, and time-sensitive planning develop the conversational skills that make time-telling practically useful.

Real-world application provides the ultimate test of time-telling competence. Learners should practice reading clocks aloud in Chinese, scheduling actual appointments using Chinese time expressions, and maintaining daily schedules recorded in Chinese to develop authentic usage patterns.

Error analysis helps identify and correct common mistakes before they become ingrained habits. Recording practice sessions and seeking feedback from native speakers accelerates improvement and prevents the fossilization of incorrect patterns.

Learn Any Language with Kylian AI

Private language lessons are expensive. Paying between 15 and 50 euros per lesson isn’t realistic for most people—especially when dozens of sessions are needed to see real progress.

Many learners give up on language learning due to these high costs, missing out on valuable professional and personal opportunities.

That’s why we created Kylian: to make language learning accessible to everyone and help people master a foreign language without breaking the bank.

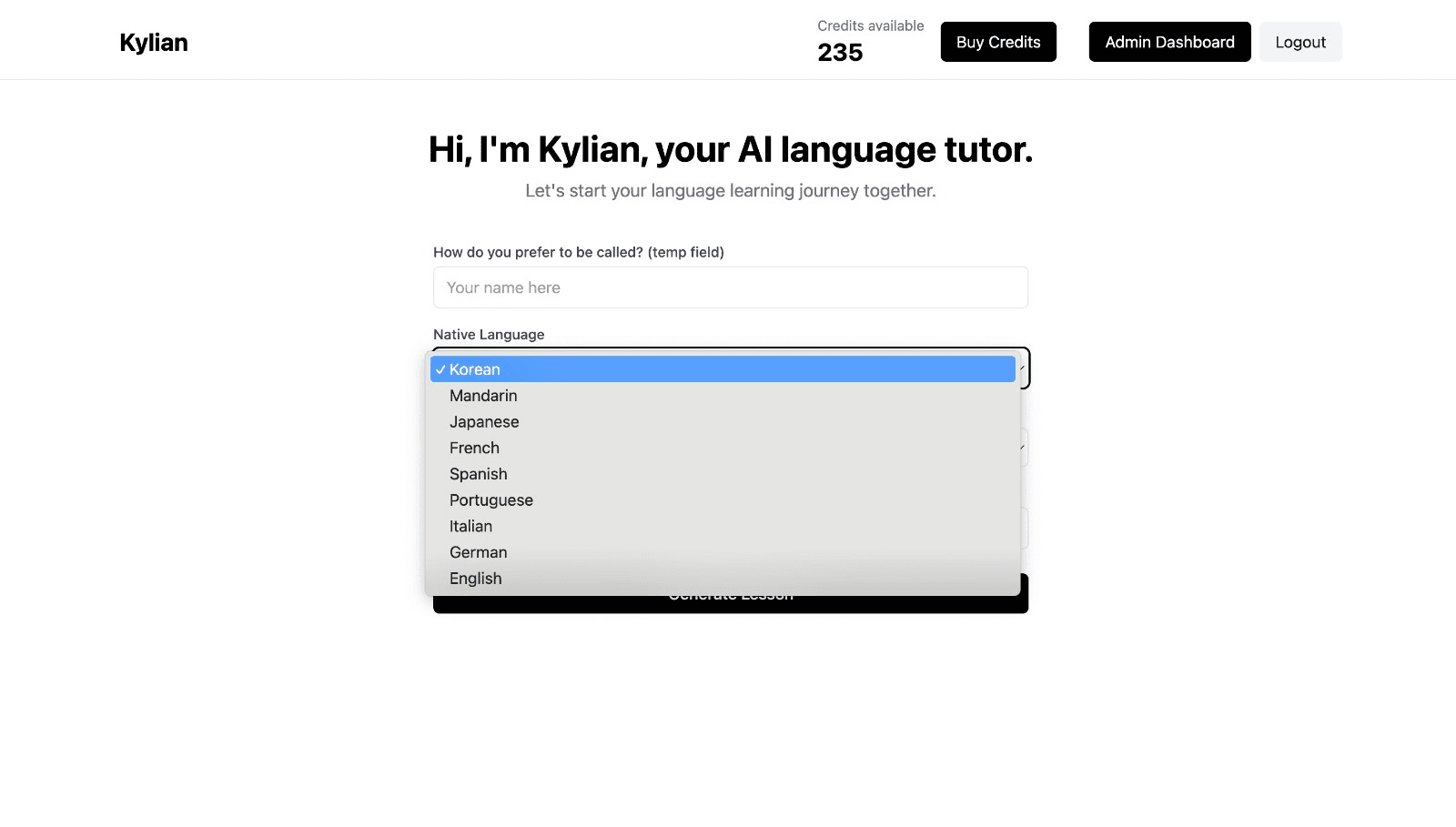

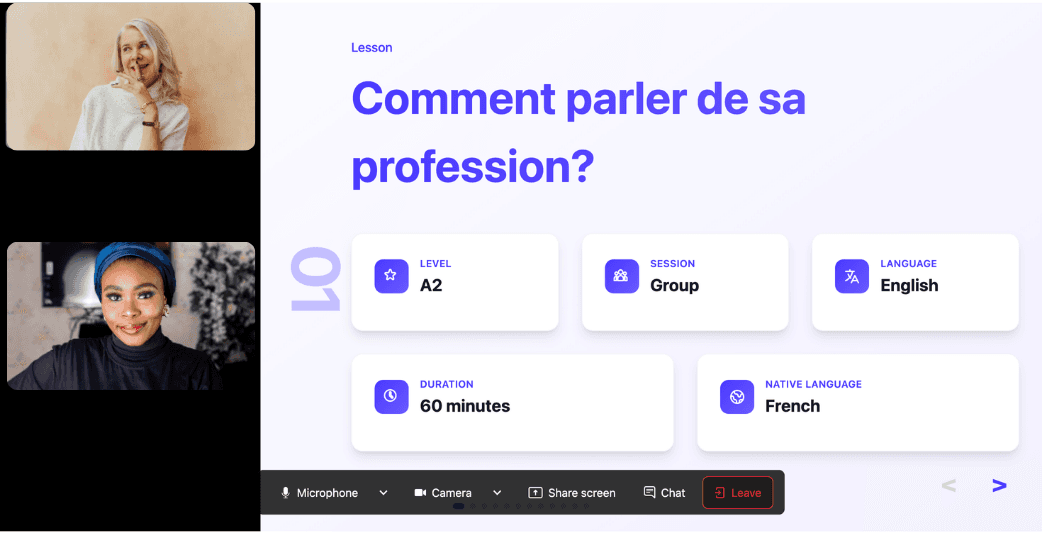

To get started, just tell Kylian which language you want to learn and what your native language is

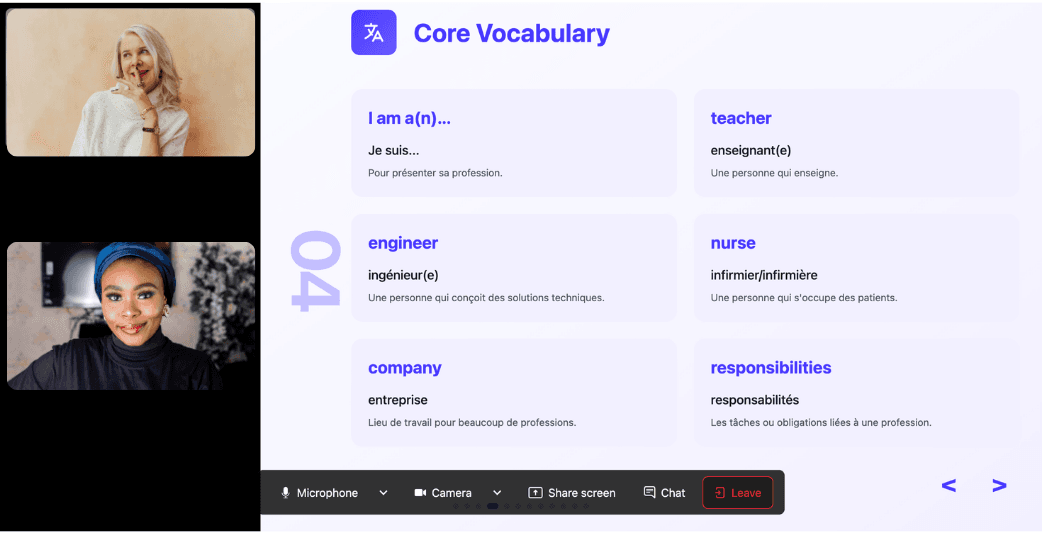

Tired of teachers who don’t understand your specific struggles as a French speaker? Kylian’s advantage lies in its ability to teach any language using your native tongue as the foundation.

Unlike generic apps that offer the same content to everyone, Kylian explains concepts in your native language (French) and switches to the target language when necessary—perfectly adapting to your level and needs.

This personalization removes the frustration and confusion that are so common in traditional language learning.

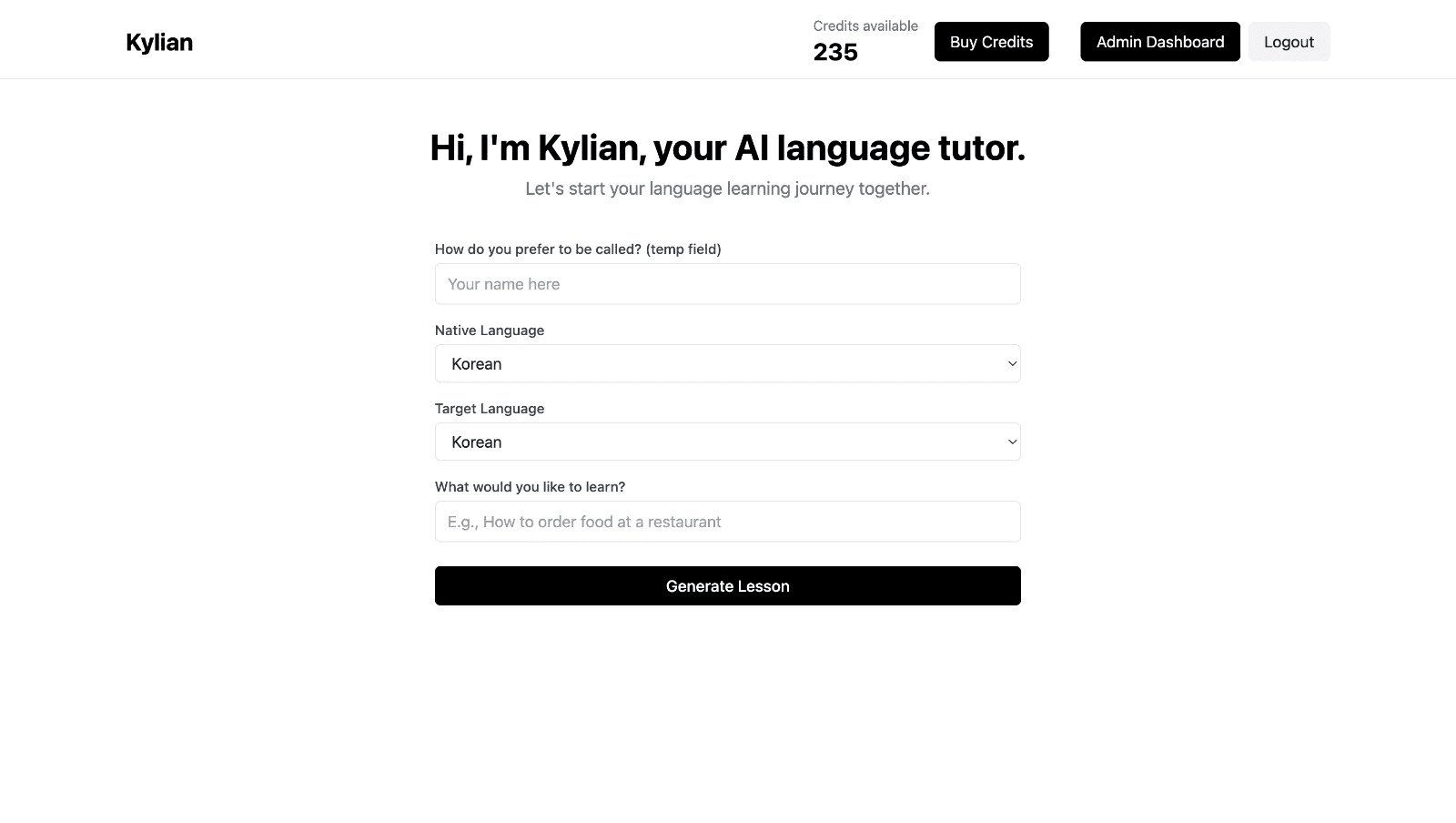

Choose a specific topic you want to learn

Frustrated by language lessons that never cover exactly what you need? Kylian can teach you any aspect of a language—from pronunciation to advanced grammar—by focusing on your specific goals.

Avoid vague requests like “How can I improve my accent?” and be precise: “How do I pronounce the R like a native English speaker?” or “How do I conjugate the verb ‘to be’ in the present tense?”

With Kylian, you’ll never again pay for irrelevant content or feel embarrassed asking “too basic” questions to a teacher. Your learning plan is entirely personalized.

Once you’ve chosen your topic, just hit the “Generate a Lesson” button, and within seconds, you’ll get a lesson designed exclusively for you.

Join the room to begin your lesson

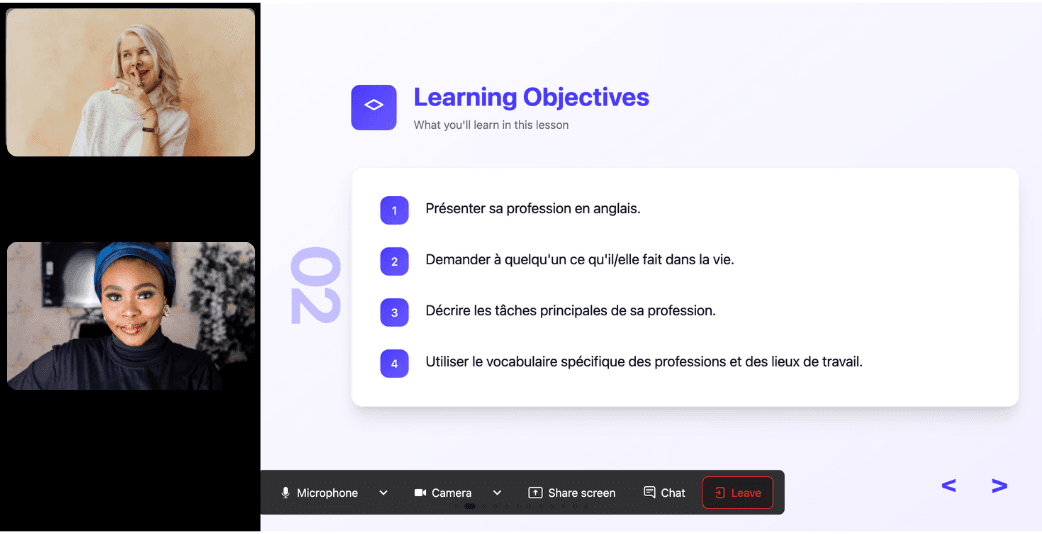

The session feels like a one-on-one language class with a human tutor—but without the high price or time constraints.

In a 25-minute lesson, Kylian teaches exactly what you need to know about your chosen topic: the nuances that textbooks never explain, key cultural differences between French and your target language, grammar rules, and much more.

Ever felt frustrated trying to keep up with a native-speaking teacher, or embarrassed to ask for something to be repeated? With Kylian, that problem disappears. It switches intelligently between French and the target language depending on your level, helping you understand every concept at your own pace.

During the lesson, Kylian uses role-plays, real-life examples, and adapts to your learning style. Didn’t understand something? No problem—you can pause Kylian anytime to ask for clarification, without fear of being judged.

Ask all the questions you want, repeat sections if needed, and customize your learning experience in ways traditional teachers and generic apps simply can’t match.

With 24/7 access at a fraction of the cost of private lessons, Kylian removes all the barriers that have kept you from mastering the language you’ve always wanted to learn.

Similar Content You Might Want To Read

How to Refer to Family in Chinese: Complete Guide

Mastering Chinese family terminology isn't just vocabulary memorization—it's understanding a cultural framework that shapes every social interaction. The way Chinese speakers address relatives reveals deep-rooted values about hierarchy, respect, and generational responsibility that Western languages often overlook. Why does this matter for language learners? Because using incorrect family terms doesn't just sound awkward—it can signal cultural ignorance and potentially offend native speakers. The precision required in Chinese family vocabulary reflects the culture's emphasis on social order and familial respect.

Learning Chinese Numbers 1-10: The Essential First Step

Chinese numbers form the foundation of language proficiency for anyone serious about mastering Mandarin. While Chinese presents unique challenges for Western learners, understanding numbers provides immediate practical value and builds confidence for further study.

Mastering Chinese Birthday Wishes: The Complete Guide

Celebrating birthdays transcends cultural boundaries, yet the expressions and customs vary significantly across different societies. Understanding how to convey birthday wishes in Mandarin not only demonstrates cultural appreciation but also strengthens personal and professional relationships with Chinese speakers. This comprehensive guide will equip you with the linguistic tools and cultural context to properly celebrate birthdays in Chinese traditions.

The More vs The Most: Key Differences and Examples

Mastering comparative and superlative forms represents a critical milestone for English language learners. The distinction between "more" and "most" fundamentally shapes how we express degrees of comparison in English, yet many learners struggle with applying these forms correctly. This comprehensive guide examines the rules governing "more" versus "most," identifies common mistakes, and provides practical strategies for using these comparative structures effectively in both written and spoken communication. Understanding when to use "more" versus "most" doesn't just improve grammatical accuracy—it enhances the precision and sophistication of expression, allowing for nuanced communication across various contexts from academic writing to everyday conversation. The ability to make appropriate comparisons reflects an advanced command of English and contributes significantly to communicative competence.

Master the Spanish Subjunctive: Your Complete Guide

The subjunctive mood in Spanish strikes fear into the hearts of many language learners. Yet, this grammatical feature is essential for anyone seeking to express nuanced thoughts in the world's second-most spoken native language. Without it, communicating doubts, possibilities, emotions, and hypothetical situations becomes nearly impossible. This comprehensive guide will demystify the Spanish subjunctive, transforming it from an intimidating obstacle into a powerful tool for authentic expression. With clear explanations, practical strategies, and relevant examples, you'll gain the confidence to use this grammatical structure naturally in conversation. Ready to elevate your Spanish to the next level and communicate with greater precision? Let's begin.

Friends' vs Friend's: Which is Correct in English?

The apostrophe placement in possessive forms represents one of English grammar's most persistent challenges, yet understanding the distinction between "friends'" and "friend's" fundamentally determines whether your writing demonstrates precision or perpetuates confusion. This grammatical decision point affects every native speaker and language learner, making mastery essential for professional and academic communication. Why does this matter now? Because imprecise possessive usage undermines credibility in an era where written communication dominates professional interactions. The difference between these two forms isn't merely academic—it's the difference between clear, authoritative writing and ambiguous messaging that forces readers to decode your intended meaning.